Eye For Film >> Movies >> Bonhoeffer: Pastor. Spy. Assassin. (2024) Film Review

Bonhoeffer: Pastor. Spy. Assassin.

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

To live a religious life, and take full responsibility for that as opposed to simply following instructions from a religious authority figure, is necessarily a complicated thing. It requires constant reflection, a living effort to interpret the world and morality in accordance with one’s creed, and that’s a difficult thing to reconcile with the much simpler notions of right and wrong ordinarily served up in the context of cinema. Todd Komarnicki’s Bonhoeffer: Pastor. Spy. Assassin. is a small film with big ambitions, and it arrives in cinemas atop a wave of controversy due not just to the grammatical horrors of its title but also to its uneasy relationship with the Zeitgeist.

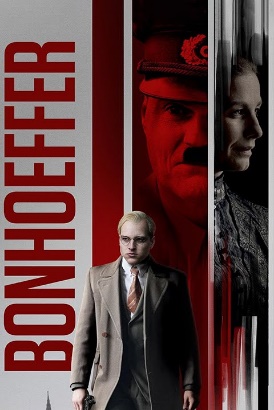

The real life Dietrich Bonhoeffer was a prolific writer, so we know a good deal about his interior world, but rather less about his actions in Nazi Germany and the compromises that he may or may not have made in an effort to stop Hitler. He was certainly involved in smuggling Jewish people out of the country, something that gets relatively little attention here despite being one of the stronger story strands, and he ultimately came to support the idea of direct action to overthrow the regime. But how are we to interpret the film’s poster, which sees him holding a gun? To someone familiar with his work, it might be a reference to his internal struggle, his acknowledgement of the reality of a violence he did all he could to stop. To the average filmgoer, however, it makes him look like yet another macho hero preparing to kill his enemies. These two things do not sit easily together.

Still more problematic is the positioning of such imagery within the context of a world where the far right is rising again and there is serious discussion of potential conflict. Right wing figures have already used it to try to claim Bonhoeffer as one of their own, prompting both the film’s cast and Bonhoeffer’s surviving family members to express outrage. Meanwhile, historians both ecclesiastical and secular have expressed dismay at the crude way the film presents a sophisticated thinker. That said, the film is clearly striving to inspire viewers to find the courage to resist tyranny, and does promote the theologian’s values of inclusivity and fairness at a time when they are sorely needed. Might it still do some good?

All of this feels somewhat moot when one watches the film itself, because although it’s definitely a step up from the self-congratulatory tedium of most explicitly Christian cinema, its ability to inspire is no greater than that of the average tearjerker TV movie playing at lunchtime on cable. It opens with scenes of the hero as a little blond moppet being playfully chased around a large house by a brother who is about to be called up for service in the First World War. There are no prizes for guessing what happens next, and it’s played out by numbers, right down to the angle of the farewell shots and the colour of the light. Little Dietrich declares that he will never play his brother’s favourite song on the piano again.

We jump about in time, with the main narrative split between Bonhoeffer’s student years (he’s now played by Jonas Dassler), scenes set on a bus in Bavaria as he’s being transported by Nazi soldiers, and scenes in Flossenbürg concentration camp. The student section puts a heavy focus on his time in the US, studying at Union Theological Seminary, and whilst this has understandably been criticised for its heavy-handedness in addressing his discoveries about US racism, it has a certain value given how few other films link the US and German experiences. Hitler was open about finding inspiration in the history of American chattel slavery, yet this rarely makes it into US accounts; having Bonhoeffer connect these things is perhaps more palatable for US viewers, and one hopes that for some it will be a gateway to learning more.

Bonhoeffer’s absence from Germany also means that, on his return, he (and therefore the audience) is able to take in the changes that have occurred there with a degree of shock, rather than watching them build incrementally. Conversations with his family members (who, sadly, do not otherwise get their due) provide a contrasting perspective, though they too are horrified. We then go on to see how his initial impassioned yet naïve attempts at protest give way, under the tutelage of his elders, to more sophisticated forms of subversion. Meanwhile, both his personal situation and Germany’s grow bleaker, a fact of which the cinematographer is at pains to remind us. Bonhoeffer struggles with his faith, but less in the manner of a great thinker and more in that of someone who writes quotes for inspirational posters.

There’s a lot of well-intentioned stuff here, and plenty of room for Angel films to learn from their mistakes and build on what they got right. Had the film centred instead on some less complicated hero – of whom there is no shortage – then it might have been moderately successful. As it is, Komarnicki has bitten off more than he can chew, and the result is overcooked, stodgy and bland.

Reviewed on: 21 Nov 2024